Why Our Education System Must Design for Coordination, Not Just Choice

The next decade in education will not be defined by whether it becomes more dynamic. It already is.

Education Savings Accounts (ESAs) are expanding across 16 states. District enrollment is declining not just from falling birth rates, but also because families are exploring alternatives. Recent federal calls for AI literacy and workforce preparation signal how rapidly demands are shifting. Meanwhile, state and local school boards face impossible trade-offs: four-day weeks, consolidated buildings, and staff stretched to their limits.

The question isn’t whether change is coming. It’s whether public systems will be active participants or passive casualties.

Right now, we’re designing for fragmentation. In 10 years, well-resourced families will assemble rich learning experiences across consumer platforms, microschools, and specialized programs. If we continue down this path, most others will rely on increasingly underfunded traditional systems operating with reduced hours and offerings. Two tracks emerge: one flexible and private, the other essential but reactive.

But there is another path if we’re willing to rethink what public education can provide.

From Systems to Networks

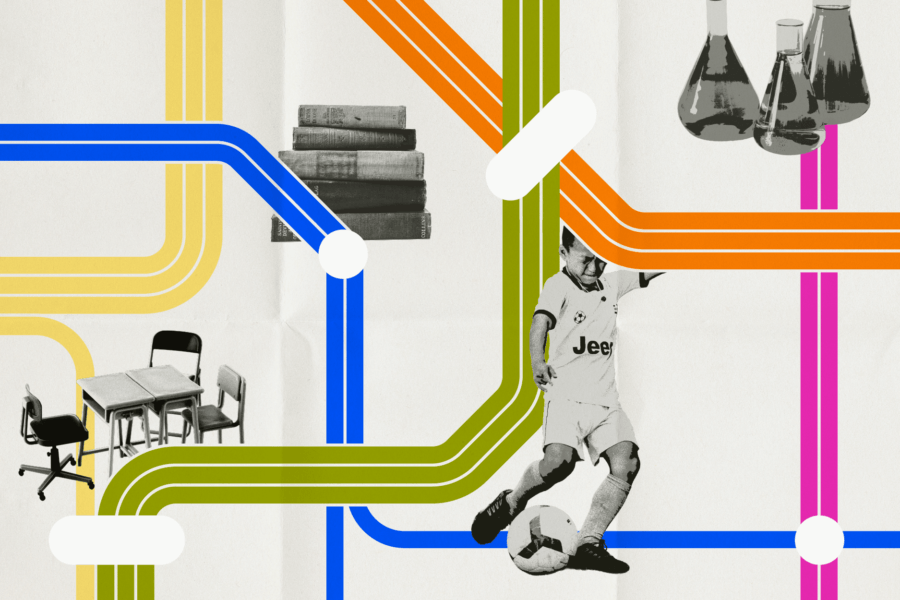

Consider a world where all ESA dollars can flow to public schools for part-time offerings. A family might use these funds for a district-run soccer team and science lab twice a week, a microschool for humanities, and an online provider for language learning. Districts would coordinate transportation, track progress, and manage IEP services across providers — capturing partial funding rather than losing families entirely.

This isn’t just theory. It’s an emerging practice that points towards the possibilities of an entirely different model.

In Utah’s Wasatch County, ESA students can enroll in individual public school courses if space allows, with districts issuing invoices through a digital platform for seamless payment. Students may receive $4,000 for non-public expenses while accessing specific district offerings like advanced sciences or sports teams. The new Texas ESA framework goes further, requiring districts that participate to offer services in an “unbundled way” that doesn’t count ESA students as full-time enrollees.

For all the talk about their deficits, districts have many assets: Six billion square feet of community-embedded space that includes science labs, art rooms, libraries, auditoriums, and gymnasiums. Trusted relationships with families. Expertise in serving diverse learners, including those with disabilities. The infrastructure to provide full-day coverage that working families depend on.

Instead of fighting the choice movement, what if districts became its backbone?

Early Adopters and Emerging Technology Stack

The tools are emerging faster than the policies. Companies like Odyssey and ClassWallet already manage ESA transactions across education providers in several states, offering searchable databases of approved expenses and vendors. Utah has solved the funding complexity by prorating ESA awards based on public school usage, ensuring seamless coordination without duplicate funding. North Carolina’s ESA+ is designed exclusively for students with disabilities and includes co-enrollment options that vary by district policy.

If more policy frameworks that encourage this coordination arrive, we will see a wave of innovation built around existing eligibility and payment systems.

Software is essential to helping states stay up to date on where students are being served, and ensure funding platforms are integrated closely with enrollment systems. As student mobility between different programs becomes more common, timely, accurate, and auditable funding becomes a critical component of trust and success.

Managing distributed learning at scale will require a deeper set of tools. Imagine resource grids that identify when science labs are sitting unused, when three families need transportation to the same specialized program, or when community-based organizations can rent athletic fields, idle classrooms, or vacant auditoriums. Currently, the logistics required to coordinate IEP meetings, related services, tutoring, or special education evaluations are overwhelming.

Unified intelligence layers will also emerge. As learning becomes more distributed, smarter tools will start connecting the dots. Today far too many students don’t get flagged for testing, 504 plans, or supplemental help. Not because they don’t need it, but because teachers are asked to do far too much and nothing seems too urgent enough on its own. New technology will help surface these hidden gaps early and provide clear, evidence-based steps for parents and educators to take action.

The coordinated approach also requires acknowledging that most families need full-day coverage. Any alternative model, no matter how innovative or engaging for kids, must solve the childcare reality. States and districts that embrace their role as community platforms — offering before/after care, coordinating schedules and transportation, providing consistency — have a sustainable advantage.

A Different Kind of Competition, a New Path Forward

This approach doesn’t eliminate competition; it changes the game. Instead of trying to be everything to every student, districts compete on their unique strengths: inclusive community spaces, trusted relationships, support services, critical infrastructure, and the ability to coordinate across providers.

Co-enrollment offers a promising way to re-engage families, but its financial sustainability depends on more than vision. Districts still face fixed costs that partial funding alone won’t cover. To make this model work, states would need to update funding formulas, create cost-sharing mechanisms, and invest in shared infrastructure, ensuring districts are compensated not just for enrollment, but for the value they provide across a more flexible ecosystem.

The alternative is continued fragmentation. Districts will serve a shrinking population with growing needs and declining resources. Staff will be asked to do even more with less. The most vulnerable students will be left in institutions that increasingly resemble last-resort safety nets rather than vibrant learning communities.

The choice movement isn’t going away. The question is whether public education will help shape that landscape or be shaped by it.

As the nation becomes more diverse, so have the needs of families. Public schools shouldn’t be asked to do it all. They should do what they do best: serve as trusted anchors as an essential, sustainable part of a more connected learning ecosystem.

The window is open to design for coordination, not just choice. For integration, not fragmentation. Public education requires a renewed optimism, and with the right policy changes and committed builders, it can thrive.