This post was originally published in the Grounded newsletter.

When we posted our article last year, “Barbie was the first avatar,” we had no idea that Barbie was in production—much less that it would become the highest-grossing film of 2023 and an all-encompassing cultural phenomenon. Naturally, the Grounded crew watched it together and, as fate would have it, the movie sparked the idea for our next piece (note to reader: this piece is delayed by months). If you haven’t watched Barbie yet, 1) you really should and 2) the rest of the article has some spoilers (sorry, but, again, you’ve had months!).

Despite its title, the movie spends a lot of time following the actualization journey of Barbie’s other half Ken. Ken lives, along with all the other main characters, in Barbieland where the “Barbies” lead all major parts of society: they are the president, astronauts, lawyers, and Supreme Court justices. And the primary identity for “Ken” is to be a partner to Barbie. In the absence of true purpose, Ken embarks on an interesting (and sometimes painful) journey of finding himself. When he enters the real world, he latches onto the concept of the “patriarchy,” because he believes it to be the source for male purpose and power in society. However, when he tries to bring it back to Barbieland, he realizes it doesn’t give him the sense of purpose he was looking for. It just creates a rift between him and the people he cares about.

We found this journey insightful because it highlights how difficult the process of finding your purpose can be, how lonely not having purpose can make someone feel, and, most consequentially, how dangerous the lack of purpose can be depending on how that person fills that void.

In this piece, we argue that finding “purpose” has become increasingly difficult over the last 50 years—a shift with drastic implications on our collective mental health, civil society, and the strength of our community fabric. While we are not the first to make this point (writers like David Brooks and many others precede us), we will uniquely extend the argument by examining the impact on young people and their search for a solution.

This emerging generation opts to look backward rather than forward. By leveraging the power of nostalgia and modern-day technology, they’re aiming to bring a sense of control to their current uncertain realities (that’s where Ken will come into play).

We will close by arguing that the answer is not in the past—it’s found in creating new societal engines geared towards helping people find purpose. Part II of this article will share more about what that could look like.

Finding purpose is critical to healthy human and societal development. In fact, multiple studies confirm an association between a sense of purpose and better sleep, fewer strokes and heart attacks, and a lower risk of dementia and premature death. Moreover, purpose often correlates with higher levels of emotional resilience, which provides important protection against loneliness.

And yet, only about a quarter of Americans strongly agree that they have a clear sense of purpose while nearly 40% either feel neutral or disagree.

In 1967, about 85% of incoming college freshmen said they were strongly motivated to develop “a meaningful philosophy of life.” By 2000, that number dropped to only 42% with being financially well-off becoming the leading life goal. By 2015, 82% of students said wealth was their aim.

So what happened in the last 50 years to drive such a shift away from living a meaningful life? In The Upswing, Robert Putnam and Shylyn Romney Garrett assess American life from 1870 onward across a range of sectors. They found that from the 1870s to the late 1960s, America witnessed gradual but consistent improvements across society in the form of growing community activism, social mobility, church attendance and income. In the past 50 years, almost all of those trends have reversed with increasing political polarization, income inequality and deaths of despair as well as steady declines in civic organization membership, trust in institutions, and religious attendance.

Putnam and Garrett argue that economic change and political dysfunction can’t explain these trends as they happened after these shifts started. Instead, they believe the change centers on mindset and culture. They write: “The story of the American experiment in the twentieth century is one of a long upswing toward increasing solidarity, followed by a steep downturn into increasing individualism. From ‘I’ to ‘we’ and back again to ‘I’.”

In the late 1960s, the Left was increasingly self-centered in the social sphere, while the Right displayed a more economic self-centeredness. The one common thread was a focus on the individual instead of the collective. In fact, Putnam and Garrett point out that the frequency of the word “I” in American books doubled between 1965 and 2008.

Over that same time period, an increasing focus on understanding the self, otherwise known as the “therapeutic culture,” emerged. In his op-ed “Hey, America Grow Up!,” David Brooks writes: “In earlier cultural epochs, many people derived their self-worth from their relationship with God, or from their ability to be a winner in the commercial marketplace. But in a therapeutic culture people’s sense of self-worth depends on their subjective feelings about themselves. Do I feel good about myself? Do I like me?”

This cultural shift led to the development of the “fragile narcissist,” who grounds themselves not in moral traditions and community, but rather in an obsession with oneself—their boundaries, their happiness—and ultimately aims to minimize any threats towards those obsessions. While the rise in therapy and self-care is not all bad, as there are groups of people that have immensely benefited from it, the overall cultural influence has shifted our attention far too inward.

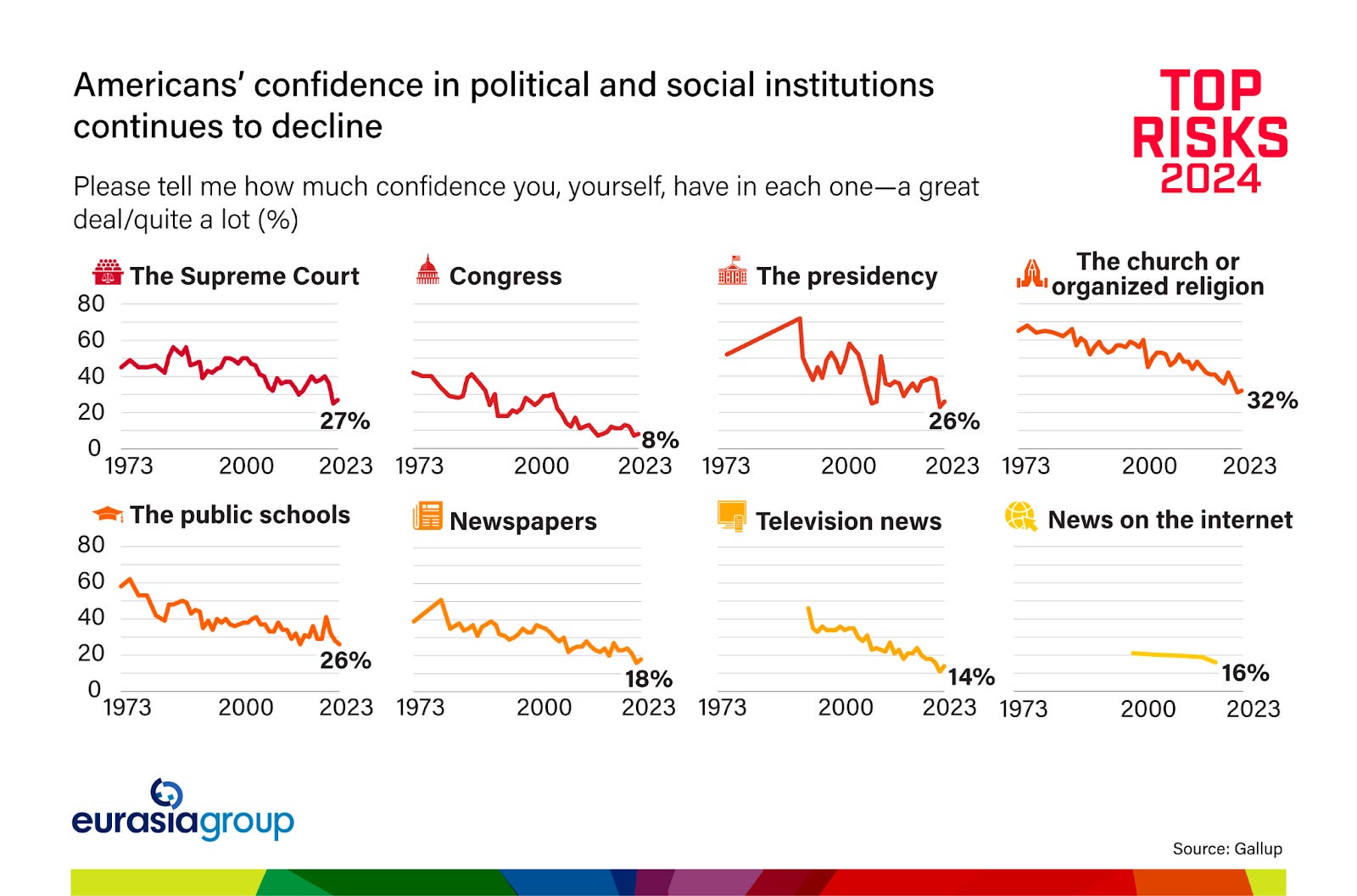

This increasing focus on the self led to a shift away from institutionalized forms of community, including a decline in membership organizations, a pushback against religion, and a serious reduction in romantic partnerships (Americans ages 25 to 54 who weren’t married or living with a romantic partner was 38% in 2019, up from 29% in 1990). Now, more than half of all Americans say that no one truly knows them. Consider the graph below—our confidence in most forms of institutions has declined considerably over the past 50 years.

Historically, these institutions played a critical role in helping individuals ground themselves in a purpose larger than themselves. So, here’s the challenge: we never replaced them.

Let’s turn back to Barbie for a moment. At the end of the movie, Barbie asks her creator, Ruth Handler, if she can become human.

Ruth tells her that she can’t in good conscience let her leap into humanhood without showing her what it really means to be human. She grabs her hands, tells her to close her eyes, and transports her through a montage of what we can only describe as uniquely human experiences captured on home video: the beauty of birth, friends, dancing, weddings, birthday parties, growing old, and even death.

These videos not only captured important life stages—they all centered on relationships. These events had meaning because they were in the context of other people—a group of young friends jumping off a bridge together, a young woman making the winning play in a bowling competition and turning around to the proud screams of her team, and a powerful matriarch dancing to the sound of her family’s and friends’ laughter at a party.

Neuroscientist Matthew Liebermen’s research on the human need for social connection found that a region of the brain, the medial prefrontal cortex, becomes activated the more a person is thinking about themselves—otherwise known as “self-processing.” While you may assume this region of the brain would become less active when thinking of others, the exact opposite happens. Lieberman explains that when we engage with others, activity in this self-centered region accelerates. In other words, we’re defining ourselves as we socialize.

Religion, marriage, and community-based organizations provide us with a foundation to ground ourselves. Religion offers a set of norms and principles for navigating life. Marriage places you in service to your spouse and your family. And community-based organizations grant a sense of accountability. These powerful mechanisms allow you to judge yourself beyond a wholly introspective evaluation.

David Foster Wallace’s now-famous Kenyon College keynote speech provides the best warning to the absence of these key institutions:

In the day-to-day trenches of adult life, there is actually no such thing as atheism. There is no such thing as not worshiping. Everybody worships. The only choice we get is what to worship. And the compelling reason for maybe choosing some sort of god or spiritual-type thing to worship…is that pretty much anything else you worship will eat you alive. If you worship money and things, if they are where you tap real meaning in life, then you will never have enough, never feel you have enough. It’s the truth. Worship your own body and beauty and sexual allure and you will always feel ugly. And when time and age start showing, you will die a million deaths before they finally grieve you.

When we diminish the roles of religion, marriage and community, we lay a social trap by creating a world where we worship the self and, unfortunately, that is not quite enough to develop a deep sense of purpose.

To be clear, the answer here is not necessarily something religious. It’s in finding and supporting institutions that provide a purpose.

A 2017 study in The Journal of Gerontology observed the rates of loneliness across 6,000 widows and currently married women in the United States. Widows, on average, tended to be much lonelier than married women with one important exception: widows who volunteered for an average of two or more hours a week no longer exhibited heightened rates of loneliness compared to their married peers. In Together, Vivek Murthy, the former U.S. Surgeon General, writes: “Helping others helps us feel competent and purposeful, and it gives our actions added meaning by extending their value to others. In short, helping others makes us feel we matter, and mattering feels good.”

Beyond purpose, norms, and accountability, these institutions give us something else very important: rituals. A ritual is a sequence of gestures, actions, or words that symbolize something important. It can be religious, but many are not. Wedding rituals symbolize the unification of two families. A quinceanera symbolizes a young lady’s transition into womanhood. A funeral honors the legacy of the dead. Rituals offer collective opportunities to reflect on important life transitions and remind us that we are not alone. With this foundational understanding, we are better equipped to face uncertainty.

Over a century ago, Polish anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski conducted groundbreaking research on the native people of the Trobriand Islands. Unlike many anthropologists at the time, he lived among the Trobrianders and studied their trading systems, morals, sexual practices, and more. One clear pattern emerged. Predictable social situations lacked rituals, but events associated with uncertainty (love, illness, natural phenomenon or warfare) centered on them. He wrote: “We find magic wherever the elements of chance and accident, and the emotional play between hope and fear, have a wide and extensive range.” While rituals do not have a causal link to the outcome, they do hold therapeutic value.

Time and time again, research confirms the benefits of rituals to cope with uncertainty. Richard Sosis and W. Penn Handwerker found that Israeli women who recited Psalms when threatened by missile attacks reported lower anxiety compared to those who did not. Jeffrey Snodgrass and a team of researchers also found that participating in Holi and Navratri rituals among Indian refugees decreased both perceived anxiety and stress.

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it is that we are living in unprecedented times and that “uncertainty” seems to be the only certain thing. And we face that uncertainty every minute with our phones providing instant access to events across the world. But unlike in the past, we do not have the rituals and institutions to properly cope.

In his book Ritual, the anthropologist Dimitris Xygalatas focuses on the diminishing influence of religious and state institutions on ritual in the modern era. However, what hasn’t changed is our collective craving for them—forcing us to confront a serious void. He writes: “New rituals are born each day, but very few of them persist for any significant length of time. The ceremonies that we see around us are the survivors: those who have made it through a long and ruthless process of cultural selection. Social engineering attempts to draw on ritual’s power are thus likely to fail unless they establish meaningful similarities to those traditions.”

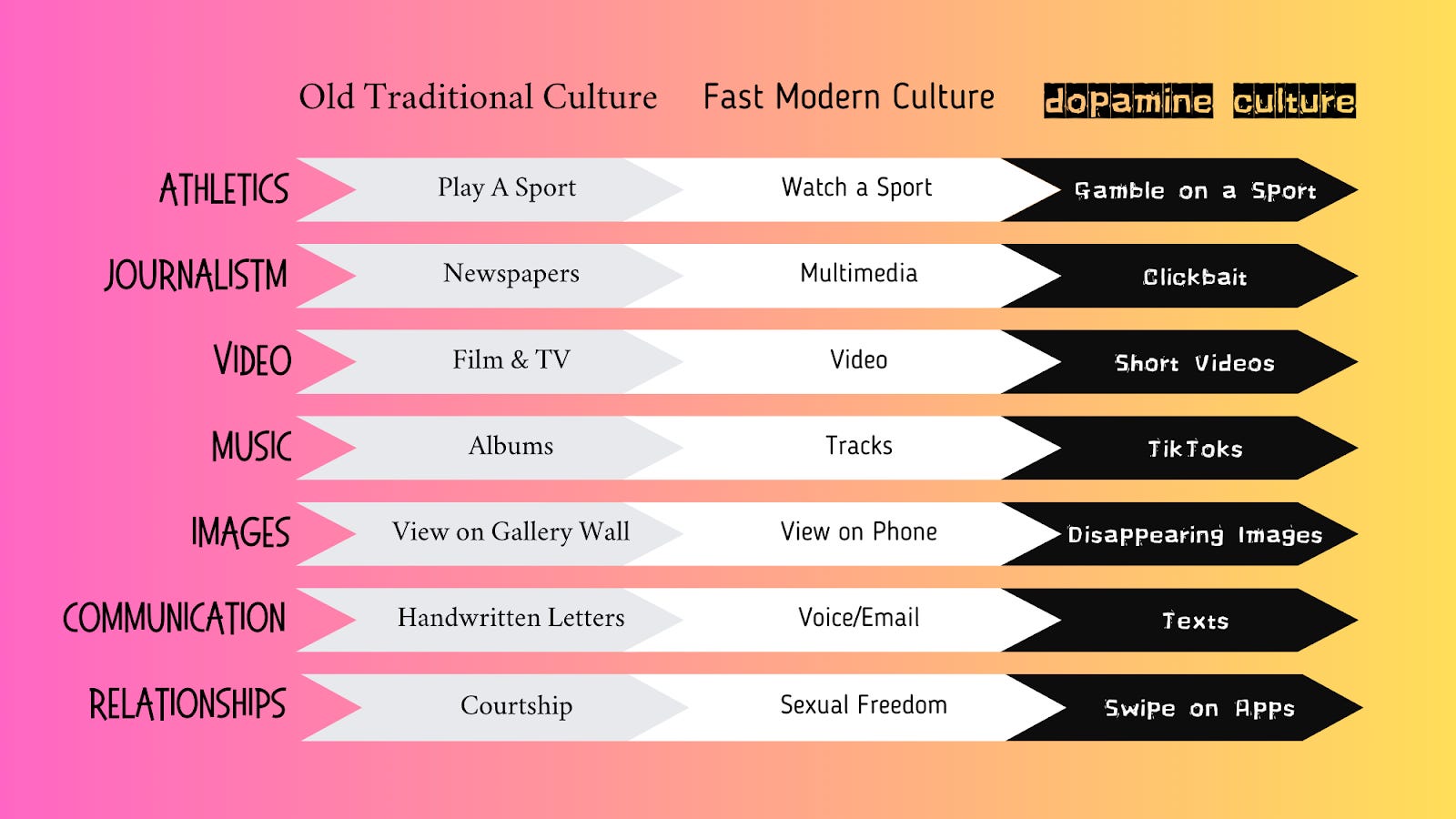

This is a particularly important point as the rise of dopamine culture has led to a widespread preoccupation with instant reward and gratification. Throughout history, societies created and practiced rituals steeped in time, deep connection, and sacrifice—none of which aligns with our current social and technological landscape.

Young people feel this void and desperately search for ways to fill it. But, similar to Ken, they look to the past for a solution. Spend a little bit of time scrolling on TikTok and you’ll notice the trend. Nostalgia has over 163 billion views on TikTok thanks to an endless amount of Gen Z accounts dedicated to showcasing the styles and vibes of decades like the 80s and even 50s and 60s. Gen Z has single handedly brought back cassette tapes, vinyl albums, and even flip phones. And when the loneliness of the pandemic hit, they didn’t turn to the shows of their childhood—they turned to Friends, a show that aired its final episode in 2004 when the oldest Gen Z was only 4 years old.

Nostalgia is a normal phenomenon with frequent links to positive social and emotional outcomes. But Gen Z’s so-called nostalgia for an era they never experienced is something else entirely: anemoia. In an interview about decade daydreaming, Andi, an influencer specializing in the looks and lifestyle of the 80s, said: “[The 80s] feels like a time when people were very connected to each other before social media… Social media is good in moderation, but I love how people seem more connected back then. They talked on the phone and met up in person more versus communicating through screens.” The comments on a TikTok account posting videos of high schooler in the 90s express similar sentiments: “notice how everything was normal and how the style was and how happy they all were 🥺.”

Gen Z’s desire to return to a seemingly more stable and connected time extends beyond TikTok videos and TV habits. Gen Z is more likely to move to rural areas in order to disconnect from devices and feel more connected with nature. They are interested in smaller college experiences that emphasize connection and physical activity over pure academic discourse and “hustle culture.” They are downloading apps like BeReal, Dispo, Lapse that harken back to the days of the disposable camera—allowing them to enjoy the moment instead of editing an Instagram picture.

Nostalgia researcher and Le Moyne professor Krystine Batcho explains: “For many people, particularly young adults or those without a financial safety net…nostalgia is a refuge, as people turn to the feelings of comfort, security, and love they enjoyed in their past.”

But this nostalgia confuses Benjamin Ho, an associate professor of Behavioral Economics at Vassar College, who states, “The way nostalgia usually works is it activates your memories from childhood, primarily the pop culture from your teenage years… It seems too soon for Gen Z to be seeking the past.” He notes that social media robs young people of unifying pop culture touchstones. With effectively infinite choices of content and experiences to consume, Gen Z lacks the shared experiences of generations past (i.e. many millennials watched Friends and TRL due to limited after-school options).

Again, Gen Z is not partaking in nostalgia, but rather anemoia—nostalgia for a time they did not experience, desperately seeking comfort in a time that doesn’t feel so noisy, unpredictable, and disconnected.

But using flip phones, wearing clothes from the 80s, or even moving out to rural areas will not fill the void. Anemoia offers nothing more than empty calories—providing momentary comfort, but not long-term fulfillment. They’ll find those answers in rebuilding and rethinking institutions grounded in purpose and authentic connection.

In the education world, we often refer to community colleges as “engines for economic opportunity” because they are affordable, based near community members, and offer a pathway to a better future. In this new, uncertain world devoid of a grounding force, we need what we’re calling “engines for purpose”—institutions that help people find a sense of purpose and community.

As promised, let’s return to Ken.

At the end of the movie, Ken realizes he needs an identity separate from Barbie. But here’s where we think the movie got it wrong: Ken was expected to explore and self-actualize on his own, a reactionary response to decades of existing in the shadow of another person. In a particularly comedic sequence, the camera pans to Ken wearing a “I am Kenough” sweater as Barbie walks off to her next adventure. In this moment, the movie reaffirms the hyper-individualist culture that we’ve grown accustomed to even though it no longer serves us.

The truth is that Ken, alone, is not Kenough. None of us, alone, are Kenough. Only when we come together to build strong relationships rooted in meaning will we get closer to Kenough. Anything short of that, well, is just Ken.