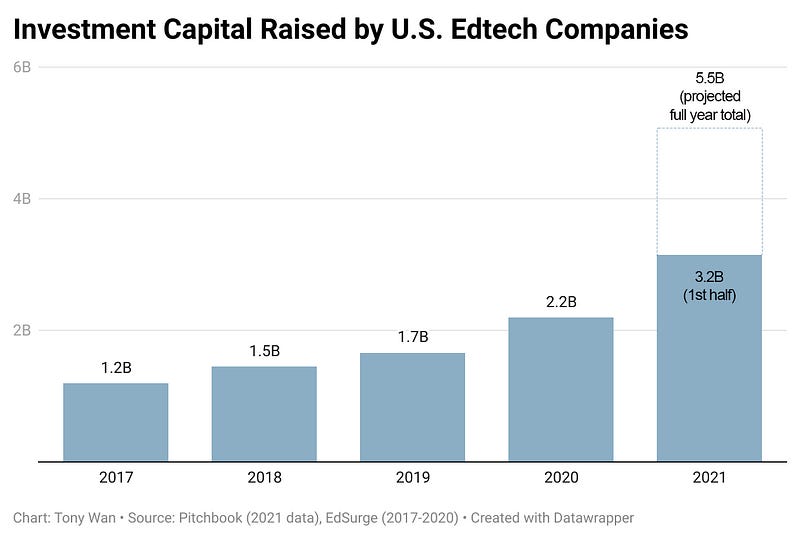

U.S Edtech Roars With Over $3.2 Billion Invested in First Half of 2021

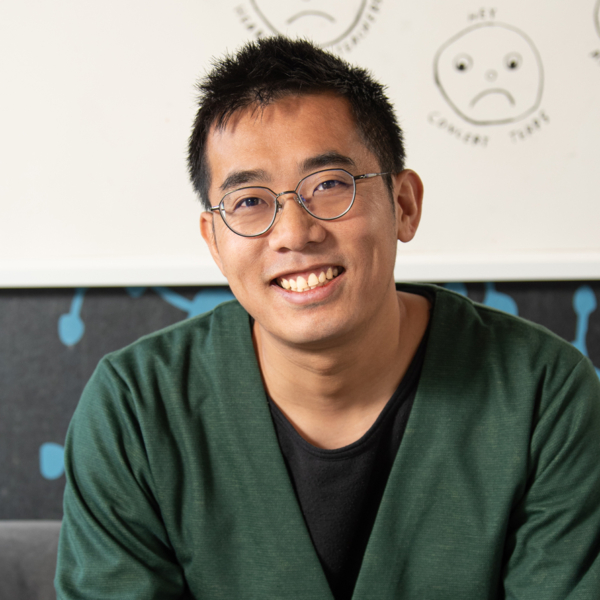

by Tony Wan, Head of Investor Content, Reach Capital

Update: Here is our data and analysis of the 2021’s full-year tally: a staggering $8.2 billion.

Over the course of two days this week, the U.S. education technology market felt as if it accelerated by more than two decades.

Duolingo, the popular language-learning app developer, filed for its IPO. So did Instructure, maker of the Canvas learning management system, which will go public (again). Meanwhile, 2U, the publicly traded provider of short courses, bootcamps and online programs from universities, paid $800 million to acquire edX, one of the original MOOC platforms in 2012. And Age of Learning, creator of the popular ABCmouse learning app for children, raised $300 million at a $3 billion valuation.

Such deals are the long-awaited outcome of a steadily growing flow of investment capital into the U.S. edtech industry. And the pace will only accelerate.

In the first six months of 2021, U.S.-based education technology companies raised over $3.2 billion in investment capital, according to Reach Capital’s analysis of deal data from Pitchbook. The tally already surpasses the $2.2 billion total that EdSurge reported for all of 2020 and $1.7 billion in 2019.

These figures are based on public deal information for U.S. companies that primarily serve PreK-12, postsecondary and workforce education. It does not include angel investments and funding rounds currently in progress, and does not encompass all the startups that provide an increasingly broad range of “training” services (from personal fitness to firearm training, for example).

School closures and the scramble to support remote learning, which led communities to use digital tools en masse (some for the first time), undoubtedly fanned investors’ interest in the education technology sector. This was not limited to formal education. Adoption of online learning services extended across children and consumers at home, and employees in companies that must now think about how to recruit and retain talent in an age when remote work will factor into expectations.

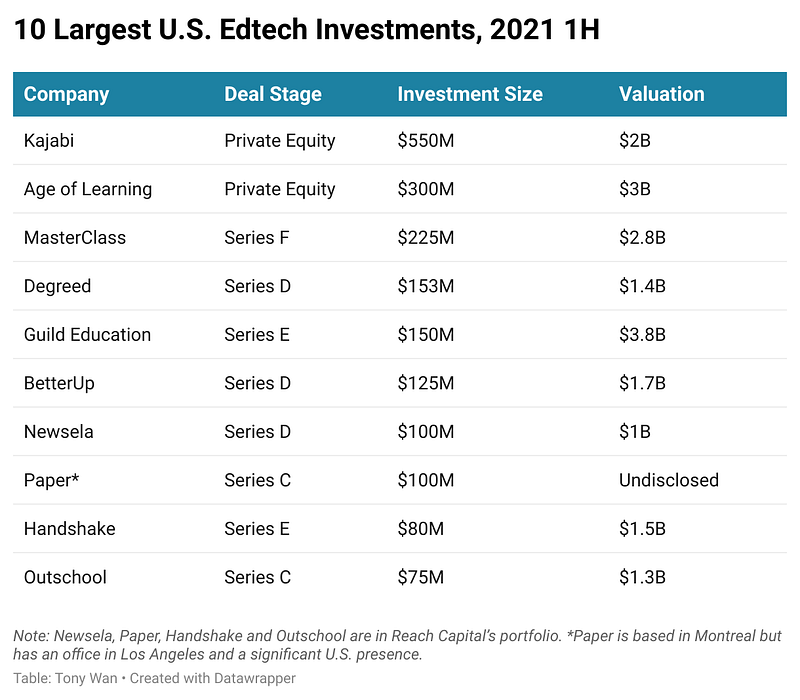

Case in point: The largest investment in a U.S. edtech company so far this year, at $550 million, went to Kajabi, a platform for business owners and entrepreneurs to create online courses. Age of Learning’s $300 million fundraise took second. The bronze medal went to MasterClass, the producer of online classes led by celebrity instructors, which raised $225 million.

The trio are followed by Degreed, which raised $153 million for its workforce upskilling platform; Guild Education, which helps companies provide higher education to their employees and secured $150 million; and leadership coaching platform BetterUp, which snagged $125 million (along with Prince Harry, who will be its chief impact officer).

As companies recover from the pandemic, learning and development has cemented its place as a top priority. At a time when there is both high unemployment and businesses are struggling to hire, there is demand for reskilling opportunities that help people find jobs that are available. But it doesn’t stop there. For employers, providing upskilling training so that employees stay is also top of mind, as detailed in LinkedIn’s 2021 Workplace Learning Report. To remain competitive, companies need to offer not just jobs, but careers.

Big Edtech Exits for K-12 and Higher Ed

K-12 and higher education were once largely viewed as no-man’s land among investors. Too much bureaucracy and too little sales efficiency, combined with too few dollars and entrepreneurial chutzpah, all contributed to the tired impression that schools and colleges were slow, even resistant, to change.

Those arguments are anachronistic, for there are now devices and dollars for edtech. A March 2021 survey from Education Week suggests that around 90 percent of U.S. K-12 districts now provide one device per student — up from two-thirds before the pandemic. The non-profit EdTech Evidence Exchange estimates that K-12 spending on education technology in the U.S. (which includes digital instructional materials, networks, devices, assessments and professional development) could surpass $50 billion this year, up from an estimated $26 to $41 billion in pre-pandemic years.

Many districts will have funds to spend. The American Rescue Plan will allocate over $120 billion for K-12 education, marking the largest single federal investment ever in K-12 education. And the FCC’s $7.17 billion Emergency Connectivity Fund for broadband is another welcome step to help the millions of students who still lack internet access at home.

In higher education, which has long wrestled with declining enrollment, the crisis has resulted in “a flight of students toward institutions that had deep experience in online education and a broad set of offerings prior to the pandemic,” as described by industry consultant Phil Hill, based on National Student Clearinghouse data. Adoption of cloud computing services for everything from online instruction to backend administration has become a priority for college executives.

The pandemic also opened up global markets for U.S. edtech products. Duolingo saw usage of its language-learning app spike across Europe, Latin America and India in the weeks following the initial outbreak. Google Classroom and Quizlet have similarly seen demand surge from schools in countries from Italy to Indonesia. As global adoption for U.S. edtech tools grows, so does their total addressable market, a key indicator of how big companies can become.

Even more convincing to investors than general trends is seeing actual returns — and 2021 has delivered several big paydays.

Coursera, a provider of online courses, certificates and degrees from universities and companies that has reached over 70 million learners, raised nearly $520 million in its March IPO and is now valued at $5.8 billion. Nearpod, a K-12 digital instruction platform (and a Reach Capital portfolio company), was acquired by Renaissance Learning in a $650 million cash deal in February. Three months later, Kahoot agreed to buy Clever, which helps schools manage and access software accounts, in a deal worth up to $500 million. Varsity Tutors, an online tutoring platform, is set to go public through a SPAC merger.

Other exits will follow. PowerSchool has already filed for an IPO earlier this year, and several other edtech SPACs are actively searching for companies to take public.

Rounding out the list of the 10 biggest U.S. edtech deals are K-12 and higher-ed companies whose footprint have greatly expanded during the pandemic. Newsela, an instructional content provider that raised $100 million, nearly doubled the number of students and teachers on its platform. Paper, which works with school districts to make tutoring support available to over a million students, also raised $100 million. Outschool, a marketplace for live, virtual after-school online activities for children, raised $75 million after a year in which bookings increased from $6 million to $100 million. Handshake, which connects students with employers across over 550,000 companies and 1,200 educational institutions, raised $80 million.

All four, as it turns out, are in the Reach portfolio.

As Exits Grow, So Do Valuations — and Competition

Education technology has never been short on hype. But it is finally reaching educators and learners at scale, and the industry is doing so while delivering financial outcomes that have eluded many entrepreneurs and investors.

Some startups are also achieving scale quickly, defying the notion that successful education companies take a decade (or longer) to build. Of the companies that raised the biggest rounds so far this year, four were founded within the past seven years: Guild Education (2015), MasterClass (2015) Outschool (2015) and Paper (2014).

This combination also means the investment market is more frenetic than ever. Where there were just a handful of “edtech investors” ten years ago, today the biggest funds are aggressively pursuing education companies — and at earlier stages. A16z (Andreessen Horowitz), General Catalyst, IVP, TCV and Tiger Global Management are just a few of the big names that have inked deals with U.S. edtech companies this year. Beyond our borders, megafunds including SoftBank and Tencent are injecting capital into education companies at a rapid clip (see: Byju’s and GoStudent).

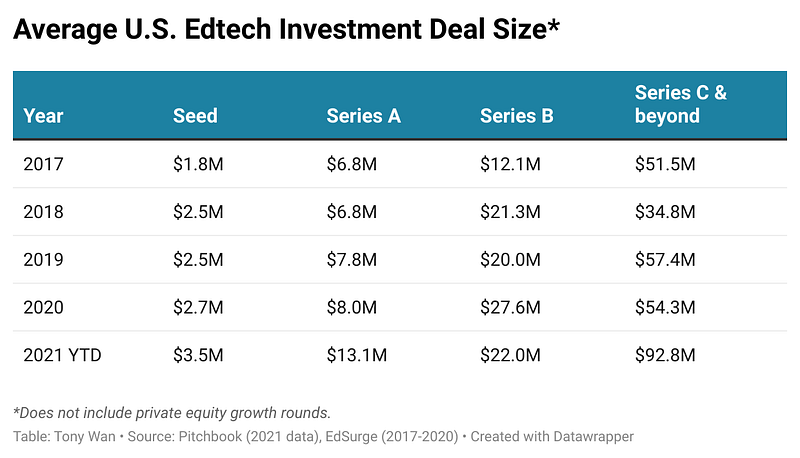

Deep-pocketed firms are now pre-empting rounds across all investment sectors, offering bigger checks in a shorter time window than is normally allotted for diligence. This is happening too in edtech. Valuations have gone up , which is reflected in increasing average deal sizes by stage in 2021.

Will This Keep Going?

The pandemic has accelerated the adoption of digital tools and services across every aspect of life, and the growth of the education industry is not confined to the U.S. Across the globe, edtech companies raised over $10 billion across 568 deals, according to market research firm HolonIQ.

Fundamental changes in how we live, learn and work have laid the groundwork for sustained growth in the education technology sector, and our optimism is informed by the following observations:

Online education is an essential option. Although experiences with online learning varied greatly due to different levels of preparation, teacher training, and access to technology, people saw that online learning can be high quality and works better for a subset of students and contexts. Parents will continue to seek digital services — and already districts are expanding virtual schooling options.

We’ve seen how technology can enable the humanity in learning — and its limits. The pandemic has highlighted the many essential roles that schools play in a functioning society — not just academics, but also food, health, social support and other custodial functions (like freeing up time so adults can work). And it has helped us identify more clearly what areas can be better served by technology (like providing on-demand access to tutors) and what can not (like fully substituting the in-person social connections that are key to emotional growth).

Tighter integration of schooling and career services will play a key role in bridging education and employment. About half of all 2020 graduates are still looking for work at the same time that companies are reporting a talent shortage. And surveys suggest that more than half of Americans would switch to a new industry if they had the opportunity to retrain. Models that integrate work projects with formal learning, along with the expansion of alternative skill development pathways outside of traditional education, will play a key role in the future of education and economic growth.