by James Kim, Partner at Reach Capital

Over the last three years, Reach Capital has been developing an investment thesis around career pathways for 21st century learners and job seekers. A repeated theme in our research has been the importance of skill development through working with employers. This appeared in our report on work-integrated learning at higher-ed institutions, and even more prominently in our report on middle skills pathways, where we described it as “work-based learning.”

That concept often goes by a more popular term — apprenticeship — and dates back to antiquity, to the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi that required artisans to teach their crafts to the next generation. Apprenticeships were structured and popularized in the Middle Ages, with adolescents employed by master craftsmen in exchange for food, lodging and formal training.

Indeed, the apprenticeship model was the primary form of job training for most of human civilization until the early 20th century, when the assembly line dramatically reduced the need for skilled labor. Going to college later became the de facto goal for many U.S. families and students; meanwhile, apprenticeships became associated with blue collar and low-wage jobs.

But apprenticeships have not gone away. In fact, we believe they will be key to creating accessible pathways to good-paying jobs in today’s economy. And their growth will be accelerated by the increasing unaffordability of traditional higher education, and acute labor shortages that leave many employers struggling to fill jobs and attract diverse talent.

In this post and the accompanying deck, we survey different components of apprenticeships in the market today, and identify the different layers of the “stack” that will be crucial to the success of the apprenticeship model. Our findings are based on two months of research and interviews with over a dozen leaders in this industry.

We define an apprenticeship as a 3- to 12-month mix of programmatic and on-the-job learning that is paid, results in a credential, and offers the potential for an immediate full-time job at that employer. Each bolded part of the definition is critical, and together set apprenticeships apart from related experiences such as bootcamps, internships, externships, and work-integrated learning in higher ed.

We also focus on tech-enabled “new collar” apprenticeships in areas such as software engineering, data science, IT, cybersecurity, tech sales and digital marketing, as they tend to be more scalable due to a lack of dependence on physical infrastructure, and since wide skills gaps exist in these verticals. Job openings for these roles are growing. In December 2020, while companies overall cut 140,000 jobs, employers in the technology sector added 21,000 jobs.

The Tailwinds Driving Apprenticeships Today

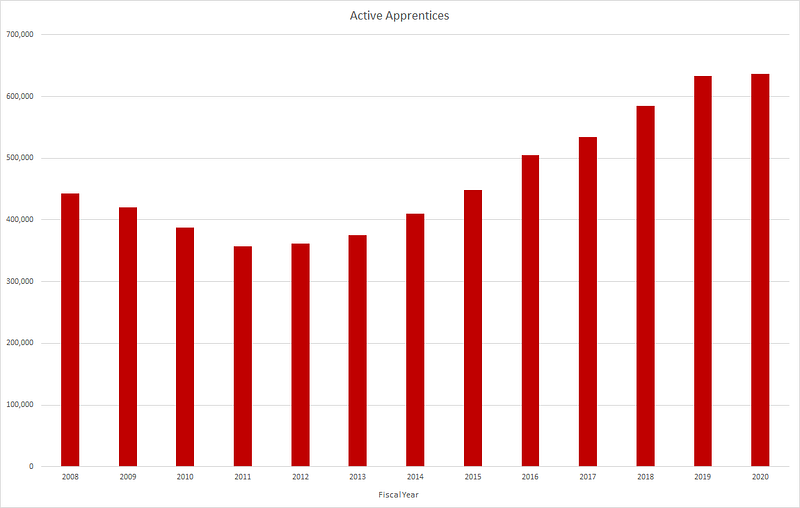

Apprenticeships have been steadily growing in the U.S., where the number of active registered apprentices has grown every year since 2011. As of 2020, there were 636,000 active registered apprentices, representing over 75% growth since 2011 at a 7% compound annual growth rate. Aggregate growth continued in 2020 despite COVID-19’s impact on the national economy resulting in a 12% decline in new apprentices that year.

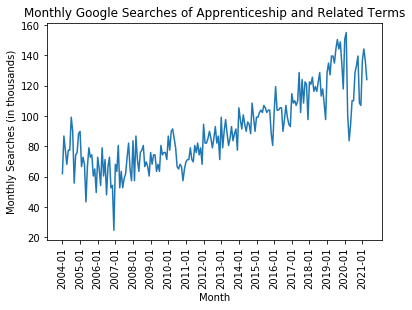

We found a similar trend in Google searches, with a 2x increase in monthly searches for “apprenticeship” and related terms in January 2021 compared to ten years prior. We view this as a proxy of demand for apprenticeships in general.

In our research, we found several drivers for the growth of apprenticeships. Young adults increasingly perceive a traditional college degree as not worth its rapidly rising cost and are attracted to shorter and cheaper (or, in the case of apprenticeships, paid) skill development pathways. Further, there is rising awareness that non-bachelor’s degree paths can lead to well-paying jobs, with 20% of technical certificate holders and 30% of associate’s degree holders earning more than the average B.A. holder.

It’s worth noting that apprenticeships and college degrees are not an either/or proposition. We found that many apprenticeship providers are recruiting current college students or recent graduates. This allows providers to bring appropriately credentialed talent to employers that still require a college degree (a diminishing share, as noted below); meanwhile, it gives candidates who do not feel they gained marketable skills in college an opportunity to earn while they learn those skills.

On the employer side, companies are experiencing acute labor shortages, especially in technical disciplines. Some have eliminated the typical bachelor’s degree requirement for certain jobs, recognizing that such a credential does not necessarily reflect one’s aptitude or ability to do the work. Employers have turned to apprenticeships to source talent, and one study has found that this approach can lower recruitment costs by as much as 20 percent.

Apprentices tend to stay longer, too. Sophie Ruddock, vice president of North American operations for Multiverse, has found that the apprentices it trains tend to stay with employers for 3 to 4 years, as compared to 1.5 years for recent college graduates.

Lastly, the social unrest of 2020 shined a spotlight on the importance of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) at all levels of society. Many employers see the earn-while-you-learn model of apprenticeships as a way to diversify their talent pipeline, as it sidesteps college degree requirements that have historically disadvantaged underrepresented candidates due to the financial and logistical barriers to accessing traditional higher education.

What Apprenticeships Need to Be Successful

We believe every successful apprenticeship provider must figure out all three layers of the “apprenticeship stack”: talent sourcing, training, and employer placement.

Sourcing

Apprenticeship providers must be able to acquire apprenticeship candidates, particularly those from underrepresented backgrounds, at scale and at low cost. Below are a few acquisition channels we learned about in our research:

Alumni referrals are a cost-effective way for apprenticeship providers to acquire candidates. And since referrals tend to be made by trusted peers or loved ones, this can help prospective apprentices feel more comfortable and confident that a program is worth it. At Year Up, a nonprofit matchmaker for students and employers, one-third of apprentices come from alumni referrals.

Community-based organizations can be effective partners for employers as they already work closely with local populations and are attuned to their needs. Churches and community centers (like the local YMCA) offer important “boots on the ground” networks and often have existing channels to reach their members about new opportunities.

- These established networks can also attract employers as they look to make good on their DEI efforts and bring more underrepresented workers (e.g. Black/Hispanic, low-income, first-gen) into their fold. In San Francisco, the nonprofit MissionBit, which provides coding education to youth living in poverty, connects its students to a tech sales apprenticeship program offered by Vendition.

Higher-ed institutions serve as a channel for apprenticeship providers to source apprentices who are already actively planning their career path and will eventually hold an associate’s or bachelor’s degree (for those employers that still require them). Community colleges, in particular, are proving to be willing partners for apprenticeship programs given that many serve an explicit workforce development mandate. For example, the Dallas County Community College District serves as one of several talent sourcing partners for the IT and digital marketing apprenticeship provider New Apprenticeship.

Training

One of the commonly stated benefits of the apprenticeship model is that the training is aligned with the job to be done at the employer. Indeed, an effective apprenticeship provider must ensure that the student is equipped with job-relevant skills. But our research has found that it must also deliver much more.

Instruction: Fundamentally, apprenticeship training must cover the skills required for the job. Further, it must teach not just the concepts but the actual tools used by employers. (A digital marketing apprenticeship program, for example, should teach commonly used tools for this trade, such as HubSpot or Salesforce.) The instruction must cover more general career skills as well, such as resume writing, interviewing and other forms of communication.

Mentorship: A repeated theme in our research was the importance of frequent one-on-one mentorship meetings for apprentices before, during, and after their apprenticeship, supplemental to any mentorship provided by the employer. An effective mentor can help make the program more personalized to students’ unique needs and circumstances — and also hold them accountable for meeting their goals.

- Reach has seen the importance of mentorship in other career training models as well. For example, our portfolio company Springboard, which offers online bootcamps for technical trades, pairs each learner with an industry practitioner for weekly live one-on-one mentorship sessions for project feedback, career planning and job search advice. Springboard attributes its high completion rates — and a $26,000 average salary increase among graduates — in part to this approach.

Community and Social Support: Unpredictable things happen in life: car breakdowns, family emergencies, relationship difficulties, mental and physical health challenges, etc. The better an apprenticeship provider can assist an apprentice through these obstacles (with services such as dedicated counselors, peer community, and partnerships with free and subsidized service providers), the more likely the apprentice will be to persist through the program.

- These kinds of support are critical — and often hard to provide. Isaac Morehouse, founder of Praxis, an apprenticeship provider for non-tech roles, went as far as to say that providing this type of wraparound support is the most difficult part of running an apprenticeship program, given the idiosyncratic nature of the obstacles involved and the fact that employers are often not set up to support employees’ emotional and mental health, thus placing the burden solely on the apprenticeship provider.

Employers

Employers are arguably the linchpin of the apprenticeship model. Without their buy-in, there are no apprenticeships in which to place apprentices, and the marketplace falls apart.

Fortunately, employers seem to be increasingly open to partnering with apprenticeship providers for talent acquisition. In our research, we found that this partnership generally takes one of two forms:

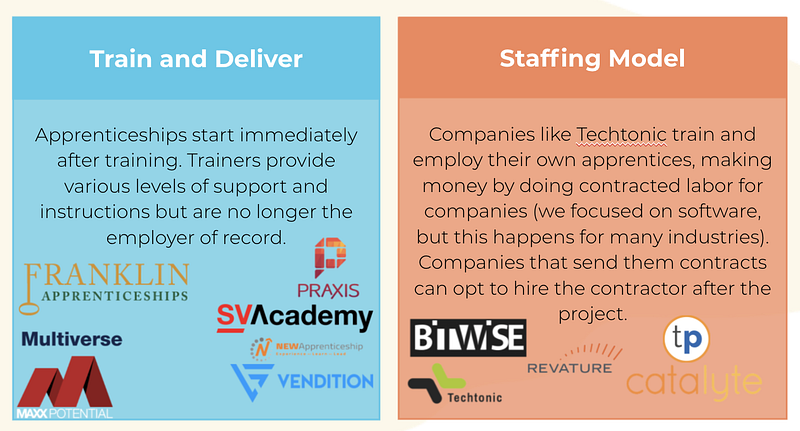

- Train and Deliver: In this model, apprentices usually go through an upfront training period provided by the apprenticeship provider, followed by placement at an employer partner who serves as the employer of record. The apprenticeship provider usually continues to offer the apprentice ongoing training and mentorship post-placement.

- Staffing: As the name suggests, this model more closely resembles existing staffing firms. Under this approach, apprenticeship providers train and employ their own apprentices to perform paid contract work for clients. At the end of a successful engagement, clients can opt to hire the contractor full-time; this arrangement may or may not be explicitly written into the contract.

Historically, the majority of attention and venture funding in the apprenticeship space have been directed toward the Staffing model, which taps into existing budgets that employers already have set aside for contractors and consultants. However, the Train and Deliver model is burgeoning, with several companies in this group expanding aggressively and raising significant venture capital. For example, Multiverse raised $44 million in a Series B investment earlier this year. We believe this model will continue to grow as employers increasingly seek help setting up their own apprenticeship programs, driven by a desire for more control over their hiring funnel, and following in the footsteps of similar efforts from Fortune 50 companies including Google and Microsoft.

What’s next?

Reach is more confident than ever that the apprenticeship model will play a significant role in the career pathways of current and future generations of talent. We believe that historical barriers to the apprenticeship model in the U.S. are falling, creating an unprecedented opportunity for entrepreneurs to build companies that connect people seeking earn-while-you-learn opportunities and employers seeking tailor-trained, diverse talent.

If you’re building in this space, please get in touch — we want to hear from you!

Many thanks to the founders/operators, employers, investors, and apprentices who agreed to be interviewed: Brad Voeller (New Apprenticeship), Christina Ortega & Cynthia Chin (MissionBit), Isaac Morehouse (Praxis), James Nielsen (Vendition), Justin Pearson (Year Up), Sophie Ruddock (Multiverse), Charlie Ackerman (Bosch), Jared Fuller (Drift), Tim Enwall (Misty Robotics), Ryan Craig (Achieve), Mariah C., Edwin E., and Julian T. Thanks also to Reach’s Head of Investor Content, Tony Wan, for editorial support.